Issue #3: Plague Days in Venice

Insights from medieval quarantine and the best mask for a pandemic

An excerpt from Amitav Ghosh’s novel Gun Island (2019) about the municipal response to plague in Venice in 1630: “They got swiftly to work, enacting measure after measure. Quarantines and curfews were put into place; all who were suspected of infection were transported to a quarantined island, while the few who recovered were sent to yet another island. All public places were closed and people were forbidden to leave their houses...The streets were so empty that plants began to sprout between the paving stones. Specially appointed marshals, whose faces were covered with beaked masks, would go from house to house, fumigating and checking for signs of the disease.” Santa Maria della Salute (above) was said to have saved the city.

In this week’s issue of These Strange Times, we are thrilled to welcome guest contributor Hannah Moots to share her insights on life under quarantine in medieval Venice. Hannah’s range of expertise is vast. As an archaeologist of health and disease, she is working at the forefront of the emerging field of ancient DNA, genetics, and archaeology, investigating the relationship between environmental change and human health. Her recent publications on ancient Rome examine 12,000 years of genetic data and geopolitical history to elucidate the dynamism of migration throughout the region as well as the genetics of malaria resistance. Hannah has worked on and taught at archaeological sites in Mauritius, Niger, Italy, the UK, and the US. She is additionally an expert on the genetics and dispersal of domesticated crops, including taro and millet. Hannah has pioneered museum education programs in NYC and Dallas, as well as created an entire program at Stanford for K-12 archaeology education and public engagement! I have been lucky to know Hannah from the time we were undergrads and flatmates in Chicago. Grace and I have delighted in countless adventures and conversations with Hannah, which have been absolutely sustaining as we all complete these degrees. Hannah is a true friend and comrade. Suffice to say: we stan. [D]

Follow Hannah at @mootspoints and DM us for PDFs of her publications!

The Lazzarettos of Venice: Daily Life in the World’s First Quarantine Stations

By guest contributor: Hannah Moots

In 1911, Encyclopedia Britannica described quarantine as a “thing of the past,” reflecting the scientific optimism at the time. While advances in medicine, including vaccines and antibiotics, have saved millions of lives and eradicated disease such as smallpox, non-pharmaceutical interventions remain an essential part of preventing the spread of new and emerging infectious diseases. Today, social distancing and self-quarantine are some of the most effective measures we can take in preventing the spread of COVID-19. Here we take a look back at the history of these practices and daily life in the world’s earliest quarantine bases, in Venice.

Lazzaretto Vecchio as seen from the Lido of Venice (all photos by Hannah Moots)

The term ‘quarantine’ itself comes from the Italian phrase for 40 days — quaranta giorni —the duration that ships carrying goods and their crews had to wait before they could dock in Venice in the 1400s. These measures were enacted in response to a growing understanding of disease transmission after the Great Plague of the previous century. The first maritime quarantine base was built on an island near Venice, Italy in 1423, known as Lazzaretto Vecchio, followed shortly thereafter by the larger Lazzaretto Nuovo. After Venice, quarantine bases were established first throughout the Mediterranean to ports such as Genoa and Marseille and then beyond.

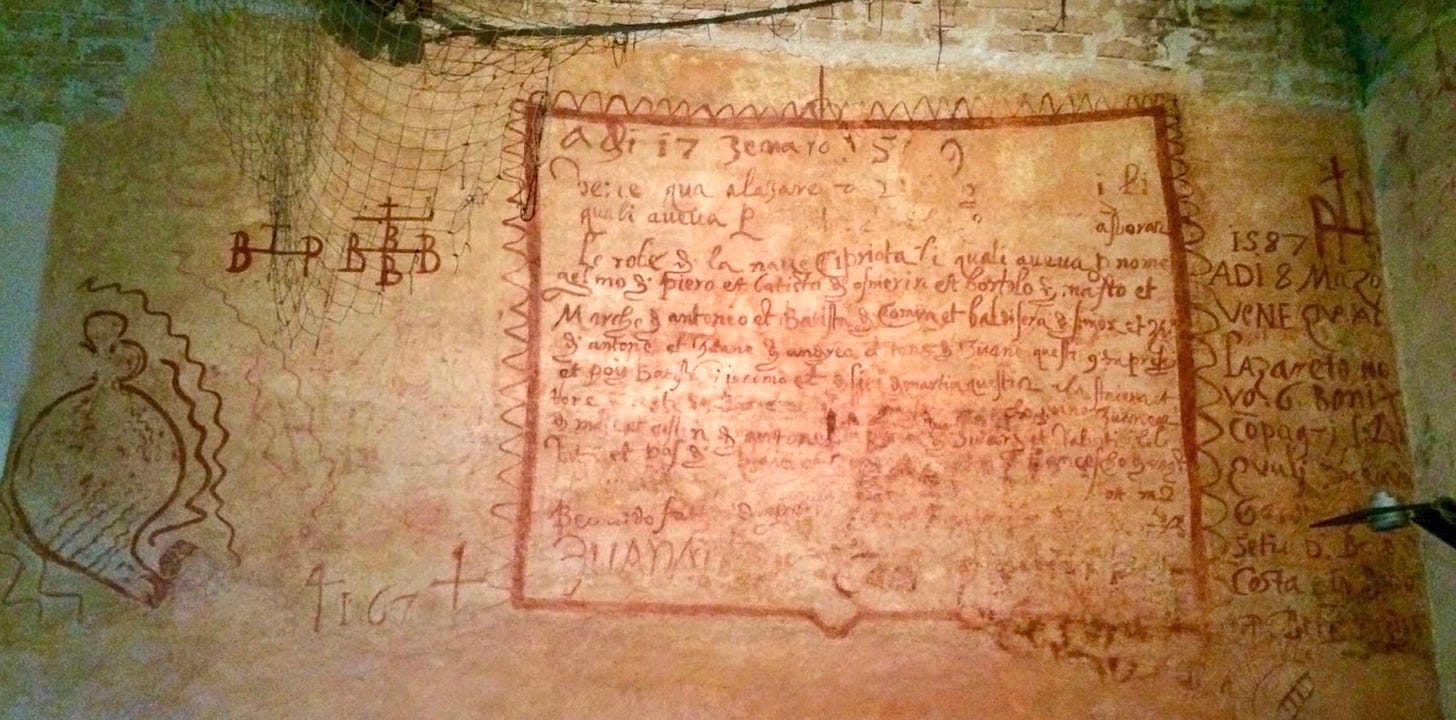

An interior view of the Tezon Grande, the main storage house at Lazzaretto Nuovo.

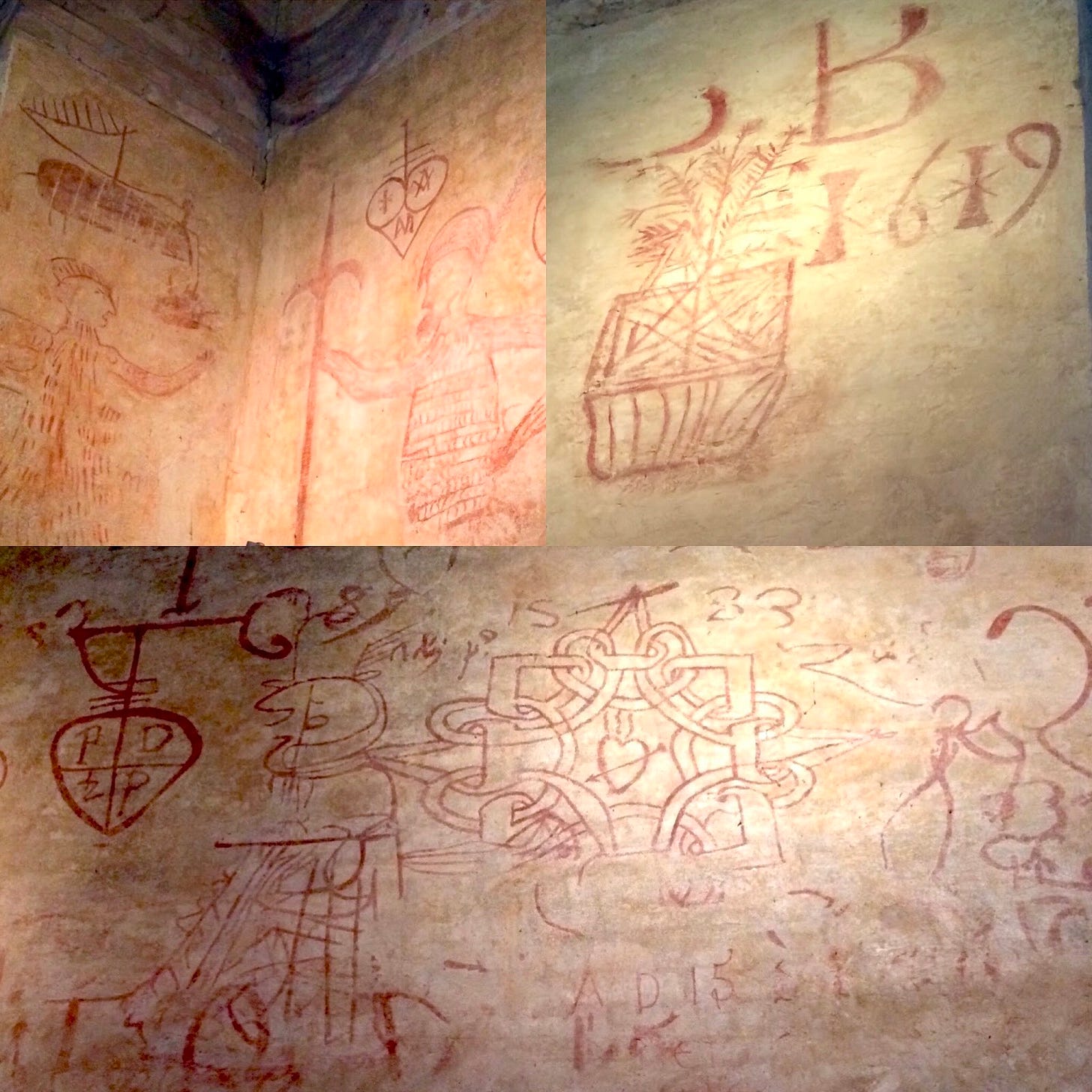

Graffiti from the walls of the Tezon Grande (the main warehouse of the Lazzaretto Nuovo) depicting shipping guild emblems, crew member names, stories of voyages and other drawings. Languages include Italian, Ottoman Turkish, Hebrew, and Arabic.

Quarantine has had dual functions since even these earliest days— as both an effective measure to prevent the spread of infectious disease and as a political tool to naturalize authority and create divisions in a globalizing world. When used as the latter, quarantine practices are both ineffective at thwarting disease spread and harmful to those targeted. Recent xenophobic comments around COVID-19 serve the same purpose as these past abuses, to create an “us” and “them” in a situation that requires global cooperation.

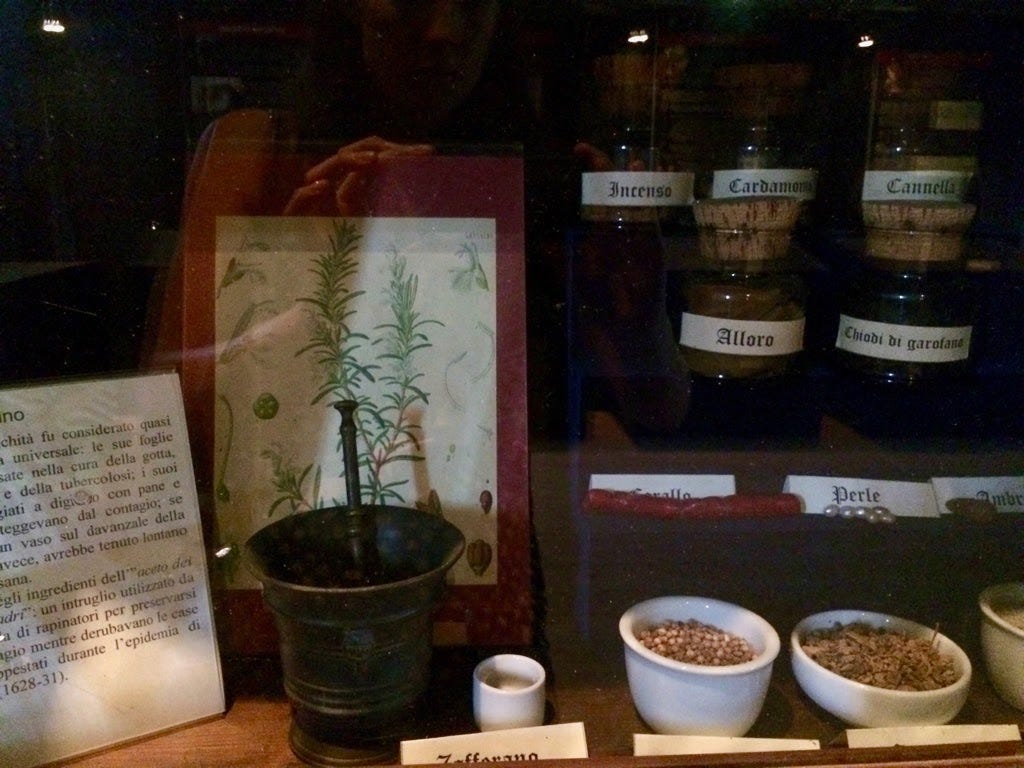

Botanicals used in Medieval medicine (and an unintentional selfie)

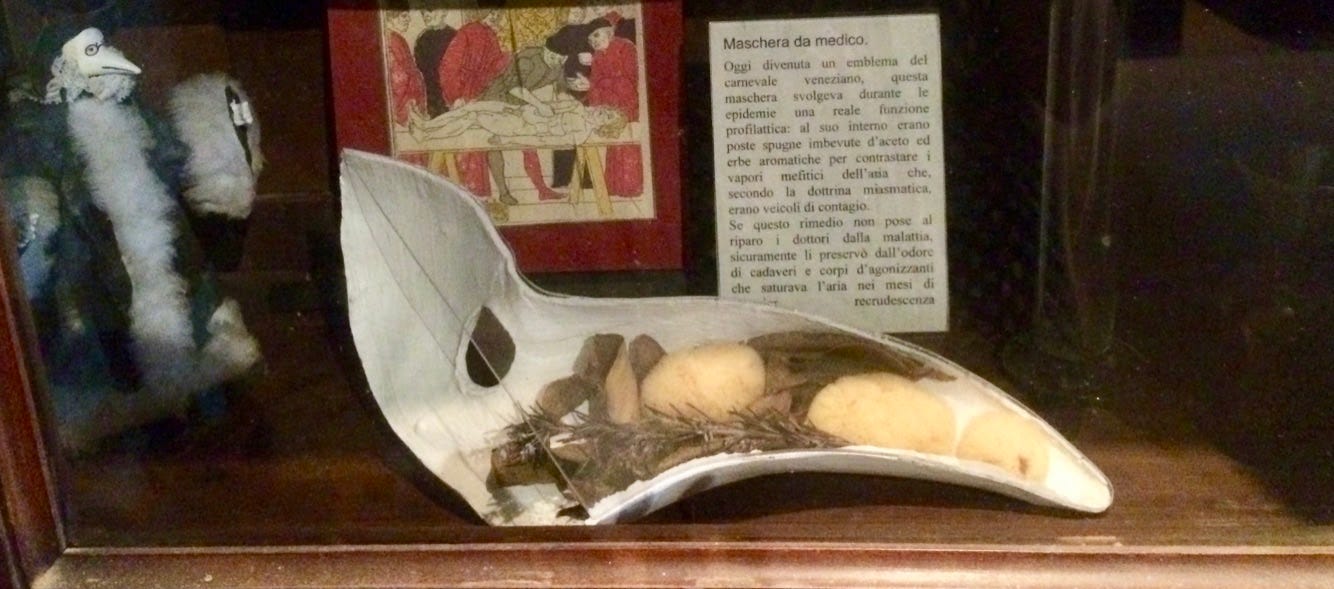

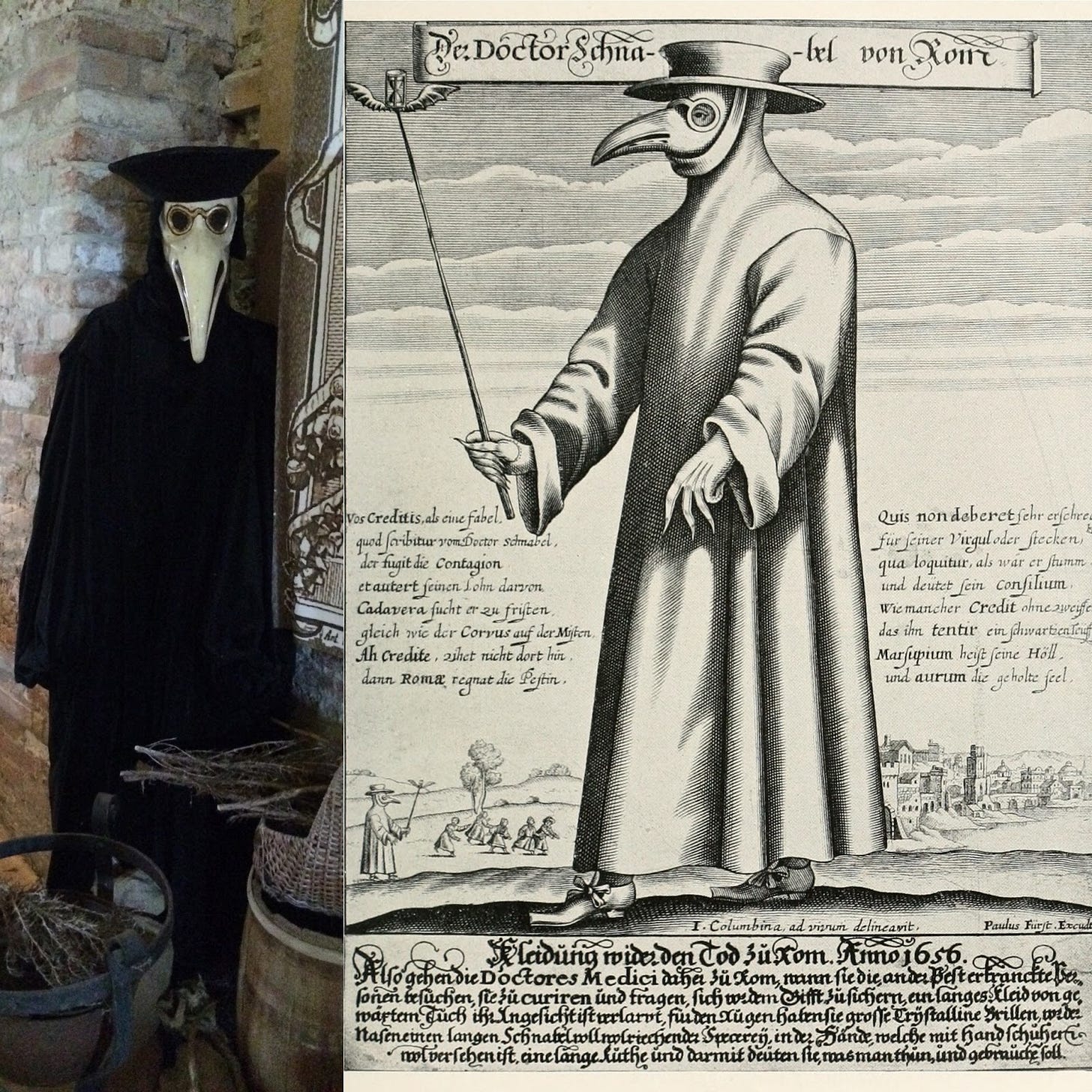

Cross-section of a plague doctor’s mask, lined with herbs and spices. Even though the garb pre-dates germ theory, the masks were worn to provide doctors with fresh air while they treated patients, which also inadvertently provided a shield from pathogens (read on for an interview with the plague doctor).

The personal effects of sailors who stayed at Lazzaretto Nuovo in the 17th century.

A view over the walls of Lazzaretto Vecchio towards Venice.

When I first visited the Lazzarettos of Venice, the lives of sailors passing time there 500 years ago seemed foreign, like “a thing of the past.” But now, I see in the objects of daily life — the die, the drinking cups, the figurines, the graffiti on the wall — people who are connecting with those they are quarantined with, who are turning to creative expression, who are scared, who are bored, who are passing the time with games and food and wine, who are hopeful that their actions will keep their loved ones and strangers alike well.

On the other side of all this, I highly recommend a visit to Lazzaretto Nuovo. More information can be found here.

An Interview with Dr. Beaky of Rome by TST

The image on the left is from Lazzaretto Nuovo taken by Hannah Moots. The image on the right is a Paul Fürst engraving from 1721 depicting "Dr. Beaky of Rome," who was an actual plague doctor from Marseille. We endorse the children in the background running TF away from him. While the plague doctor ensemble did not originate in Venice, beaked masks worn at Venetian masquerade balls today are based on these outfits.

TST: Your costume is quite interesting. Could you tell us a bit more about it?

Dr. B: Ah, yes. This is hot off the runway at fashion week. Unfortunately, the event was cancelled, but I still get to wear this incredible outfit, as you can see. The overcoat is made from a light waxed fabric. My favorite piece is the mask with these glasses built in. Now I hear that it’s all the rage across Europe!

TST: We noticed you are holding what looks like a magic wand. Does it serve a particular purpose?

Dr. B: I was just using this wand to examine a patient! It creates some distance between me and someone who might be afflicted. It also comes in handy for waving people off who are trying to get too close!

TST: We need some wands for maintaining social distance! What do you enjoy most about your job?

Dr. B: I’m a municipal employee and the pay isn’t too shabby! Each day I get to treat aristocrats in their mansions as well as ordinary folk in their homes. My skills are always sought after...unfortunately, I suppose.

TST: And what are the biggest challenges of your work?

Dr. B: When people see me they usually run away or scream because everyone is afraid of the plague. I’m not offended. It makes sense. I’m also worried about being kidnapped because I’ve heard my colleagues in other cities are being held for ransom since our services are in such high demand. Honestly, I’m tired of the rich and their antics.

These Strange Times is a collaboration between us, i.e. Grace H. Zhou and Dilshanie Perera, cultural anthropologists and writers based in Oakland, California. This is our project to deprogram, reground, and reengage the world through collaboration, care, creativity, and community. Thank you for joining us!